|

|

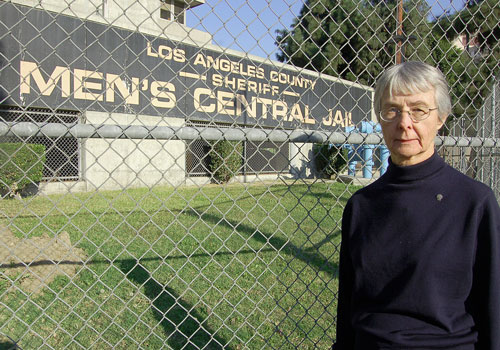

Bringing light to the 'House of Sorrows' --The Tidings / December 2006 Story & Photos by Bill Stephens

Inside L.A. Men's Central Jail I follow Sister Patricia Geoghegan down a windowless hallway past a "No talking!" sign. Handcuffed high-security inmates led by a Sheriff's deputy shuffle past. We pass a group of general inmates.

"Face the wall! Face the wall!" a passing deputy calls to them. I follow Sister Patricia to the Catholic chaplain's office, a Spartan room with old desks, two space heaters, and a mural of Jesus calming the apostles. A religious literature cart stands ready to roll. An inmate sits down across from silver-haired 75-year-old Sister Patricia, who's dressed in a blue turtle neck and long blue skirt. "What can I do for you today?" she asks. "I read the book you gave me about St. Theresa of Lisieux," says the man, who's awaiting a possible life sentence. "It touched me." "Amazing, isn’t it." "When I spoke with you the first time, I was hopeless. I still worry, but I'm better." Sister Patricia promises to find him similar books. "Read Psalm 88. It's about a person who was in the "I'll read it today." After she reads part of it to him, he thanks her and leaves. She tells me: "Reading about Theresa, who suffered but kept faith, lifted him up." Psalm 88, she says, is to read when you're down. She shakes her head: "My frequent challenge is how do you minister to people trapped by the narrow gang lifestyle?" * * * * * Sister Patricia's first day at Men's Central Jail four years ago, a concerned colleague asked at lunch: "How was it?" "Fine. Actually, I love relating to these inmates." Her reaction might have been different if her life had been different. Born in Los Angeles and raised in Beverly Hills, she wanted to be a nurse. At 20 she felt called to be a Daughter of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul. So she became a nursing sister with the Daughters of Charity, who care for the poor. She worked among other things as a psychiatric nurse, nursing school director, and hospital CEO. She founded and taught at a nursing school in Ecuador, and helped start poverty hospitals in Angola and Haiti. Returning to L.A., she felt called to help inmates. L.A. County Sheriff's Department Men's Central Jail houses 6,800 men. This includes many high-security inmates awaiting trial and transfer to prison, and some serving short sentences. Educational/rehab programs are limited because inmates are in transit. "It's old and gloomy," she says. "I call it the 'House of Sorrows' because there's so much pain." Sister Patricia is one of five Catholic chaplains here, part of L.A. Archdiocese's Office of Restorative Justice/ Detention Ministry, started in the 1970s to serve Southern California's growing prison population with specialized chaplains. The Archdiocese provides 23 chaplains for 61 county, state, and federal facilities. She mostly counsels individuals, spending half her time in the office meeting with inmates, half going to those who can’t leave their cells, meeting with high-security inmates. "People ask if I'm afraid. We're at very little risk. Inmates know while we can't love their crimes, we love them as humans and God's children. "Our Chaplains have passion for the work, which includes

respect for inmates and deputies alike. "Inmates express what they want, and we try to meet their needs, giving comfort, providing reading material, counseling, referring to appropriate departments or agencies. We don’t always talk about God. But since their problems relate to the spiritual, we usually get around to that. "Our purpose isn't to promote our religion, but to

facilitate an encounter with God, if the inmate desires. Many say they can’t

pray. We help." "The Bible is a way to connect with God. So I may say: 'Read this psalm. When you come to a spot that touches you, stop and let that happen between you and God. "With some inmates, if you just listen to their story, they tap feelings that help them find themselves and answers. Most are inveterate gang members. I try to remember this person was once an innocent child before 'friends' got hold of him, and he changed. I pray that the real person can be restored." She worked with a member facing prison who was finally touched by feelings of remorse, and changed his thinking. She corresponds with him and visits him in prison, where he studies. "At times, I may lay a guilt trip on an inmate and try to wake him up. I remind him, for instance, selling drugs hurts people and choices have consequences. When you're in jail, your whole family's in jail. "Being a chaplain is heavy work because there's much pain and suffering here. But I love bringing God into inmates' lives." * * * * * In the office, a young Latino tells Sister Patricia he's worried about his family and a possible life sentence. He complains he can't pray. "Can you talk to your mother?" "Yes." "Do the same with God. Just talk and listen. Especially listen." When the inmate mentions eye pain, she checks it and suggests he visit the clinic. While Sister Patricia telephones, Chaplain Paulino Juarez-Ramirez tells me she really listens and follows through, that inmates like her maternal instinct and Spanish language ability. Father George Horan, co-director of the Office of Restorative Justice/Detention Ministry, thinks her Third World experience makes her resourceful in the jail environment. "She's compassionate, but challenges inmates to grow." Walking the jail, Sister Patricia shows me the education center. We peer down a row of high-security cells. As she strides mazelike hallways, passing inmates wave: "Hi Sister!" Deputies nod: "Mam." She greets Sergeant Daniel Pollaro. He says Sister Patricia walks the toughest rows, is brave, and never too busy to give spiritual support. Patricia chats with Deputy Chris Medina. He says religious programs help jail morale by showing somebody cares. They make our job easier, he says. I was told that later in the day, Sister Patricia walked a gang row. The men wore tattoos and downbeat looks. But when she entered the corridor they came alive. Hands reached out to greet her. Many wanted to talk. “Sister! Sister!" At a

multi-person cell the inmates were creating a seven

foot drawing of Our Lady of Grace on the cell wall. “Who's drawing it ?” she asked. “All of us.” “Beautiful." They made many requests: “Sister Patricia, help me talk to my boy." One asked for faith books. Another for communion. “Can we get Christmas cards?” One man told her his infant child died, and requested a special visit from the baby's mom. Sister Pat consoled him and said she would try. The men asked her to pray with them. They closed their eyes, moved closer to the bars, put their hands together. “Lord. Bless these men and their families for what's been done to them. Forgive

them for what they've done to others. Give them courage for whatever's in store

for them." One inmate said Sister Pat helped him. “We feel down. She comforts us." * * * * Sister Patricia now believes the U.S. criminal justice system needs to be much more rehabilitative and more compassionate to inmates and victims. To unwind, she walks, reads, listens to music, watches birds, and sees friends. "I love this chapter in my life because of the one-to-one interactions. I find God almost anywhere. I don't plan my career. I just listen when God speaks."

|

||

|

|

||