|

Where The Poor Call HomeMarch, 2009

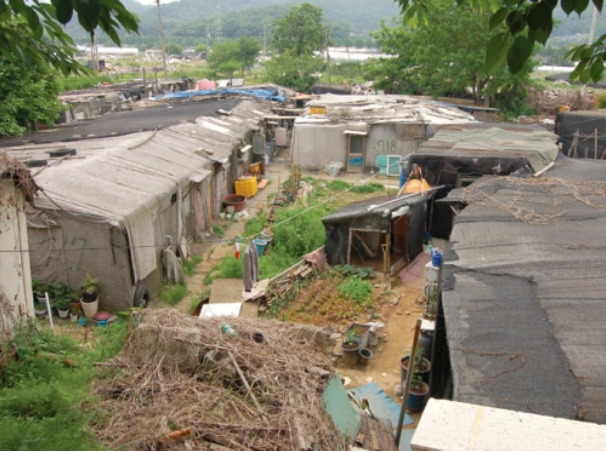

More than 1,000 people, two-thirds of them elderly, live in homes made from plywood and vinyl here in Dukpang Village. This is the first in a two-part series. Part 2 will appear in the April issue. I first visited South Korea in 1989 on a writing assignment. In the last five years, I've been back several times, both for work and pleasure. On these recent trips, I was impressed with Seoul's growing affluence and modern feel in everything from architectural touches in buildings to how the average Seoulite dresses. But I also was surprised one day as I entered the Jamsil subway station to see a homeless man sleeping on the steps. I would learn that despite the nation's status as an economic miracle, going from post-war rags to world's most wired developed nation in the last 50 years, poverty and the lack of affordable housing are major problems. With the economic growth that started in the 1960s, more and more people flocked from the countryside to the nation's capital, creating housing shortages. Rents soared. Older, low-income neighborhoods began to be aggressively redeveloped to build middle-income apartments. As a result many poor were displaced and left with few affordable options. Today, many of Seoul's poor sleep in subway stations, in tiny rentable rooms called jjokbangs or in vinyl houses. "These days more people in Seoul work irregular part-time jobs," said Shin Myong Ho of the Korea Center for City and Environmental Research (KOCER), a nonprofit independent research organization that analyzes urban issues and advises grassroots organizations and the government. "There's a growing gap between rich and poor." Chung-Ang University's Ha Seong Kyu, an urban planning professor, also said that, back in the 1980s, South Koreans would demonstrate on behalf of poor people facing eviction. But today, the average Seoulite, often impeccably dressed and armed with the latest in cell phone technology, isn't aware of — or interested in — jjokbang and vinyl house dwellers. Nonprofit and religious groups, however, continue to take up the cause. They are lobbying the government to build housing that the poor can afford and to provide direct hands-on relief. Last May, advocates from some of these groups agreed to show me this other side of Seoul. Despite the abject conditions many of these people live in, what showed through most profoundly was their resilience — and that of their advocates — to better their situation. Here are snapshots from my visits with Seoul's poor. The Street Sleepers In Seodaemun-gu, a residential and historical area in northwestern Seoul that is home to Yonsei University, I met Kim Sun Mi, who leads Silchundan, a nonprofit group of young volunteers dedicated to helping the homeless. Before the group's weekly Thursday night meeting began, the bespectacled social welfare graduate student from a middle-class family explained how, before the 2002 World Cup here, the homeless were being driven outside of the city. "We formed a group of students and social workers which successfully campaigned to block that," she said. "Afterwards, we created a permanent volunteer organization to help the homeless." The group now has 20 university students and a few ex-homeless members who meet every Thursday and then break into small groups that visit the homeless. "We approach street sleepers, offer them tea and build relationships," said Kim. "Our goal is to get them a place to live." She described a deaf homeless man her group aided. He moved into a jjokbang, started receiving welfare and later found a government job, which allowed him to move into public housing. Modest as it sounds, this is considered a success story. The following Thursday night, I headed out with four of Kim's volunteers, including the affable Shin Yoon Cheol, a recent college graduate who studied marketing. At Jogno 3 subway station, we chatted with three homeless men sitting on the pavement drinking soju, as commuters hurried past. Many of Seoul's estimated 4,500 homeless live in and around subway stations and parks. Fifty yards away we tapped on a large refrigerator-sized cardboard box. A man in his 60s popped his head out. This box is his home. He smiled and accepted our tea. Nearby, we met a man selling newspapers at a stand. "He works hard, doesn't drink," Shin said. " Still, he sleeps in the subway." Finally we came to a homeless man sitting on a blanket. Mr. Kim is 31. He's been homeless for three years. After working as a farmer in the countryside, Kim came to Seoul 11 years ago. Things didn't go well, and he ran up quite a bit of debt. He told us he's trying to find a job. "Life sucks," he said matter-of-factly. "But I try to be positive." "What do you think of these volunteers?" I asked. "They're beautiful because they understand me. They give me ideas to get out of this life — and good tea." Seven Dollars a Day Outreach volunteer Kim Sun Mi and I took a taxi to the Hwaehyun-dong area near Seoul Train Station where nearly 800 residents live in closet-sized rooms called jjokbangs that can be rented for $7 per day. We entered a four-story brick building with paint peeling off the hallway walls and walked past a shared pit toilet. At the end of the hallway was the room of 56-year-old Kim Hyun Tae, a slim man whom Sun Mi met four years ago when he was sleeping on the street. She helped him get into a jjokbang. We sat on the floor near Kim's bedroll, small television and mini-refrigerator. "How are you doing?" Sun Mi asked, patting him on the shoulder. Smiling, Mr. Kim said he just left the hospital and has been alcohol-free for eight days. "Good," Sun Mi said approvingly. Mr. Kim used to work in construction, but after an injury, could no longer work. The Seoul native said he has no family. "He's improving his life and taking better care of his health," said Sun-Mi, who helped him get a TV. "He wants to stop drinking." Suddenly, a drunk man staggered into the open doorway and began loudly cursing us. "I understand you had a bad day," Sun Mi told the man in a stern but respectful tone. "I'm sorry. But you shouldn't act this way." There are some 3,600 such jjokbangs in Seoul, according to the KOCER. In the last decade, these rental rooms have become popular with the urban poor. They house mostly middle-aged single men, according to social worker Kim Jonghan, who runs a government-backed jjokbang support center. Some are unemployed. Others work part-time in construction, as street vendors, newspaper collectors or government workers. Many lack education. About half previously slept on the street. Because some are alcoholics or have emotional problems, Professor Ha of Chung-Ang University said these people need more than housing; they also require medical attention, counseling and job training. The following week, in the Dongja-dong jjokbang area, also near the Seoul train station, volunteer Shin Yoon Cheol and I walk down a dim hallway in an old building to visit the room of Lee Wi Jun. Originally from the countryside, the friendly 50-year-old used to work in Seoul as a cook and day laborer until he was injured in a fall. Lee wants to get out of this room, but doesn't have the money yet for public housing. His child, meanwhile, is being raised by one of his brothers. Shin loaned Lee money to buy a TV and small refrigerator. After talking for about 30 minutes, we say good-bye. Lee followed us out into the dim hallway, and I could feel his loneliness. He waved as we left. Shin and I soon reached another building where we met Kim Kil Su in his tidy jjokbang. Shin told me that the hardworking Kim cleans streets and is looking for work as a security guard. Meanwhile, Shin, who visits Kim weekly, is teaching him computer skills. House of Vinyl It was a sunny Sunday in May when Lee Won Ho, an organizer for the Korean Coalition for Housing Rights (KCHR) took me to visit vinyl house dwellers. His nonprofit group helps these residents organize and fight for their rights. Vinyl houses are self-built squatter dwellings made from thin plywood covered by vinyl. In the 1980s, poor from the countryside and Seoul started settling in such places on empty land south of the Han River. Today, if you include adjacent Kyonggi province, some 35,000 people live in nearly 10,000 vinyl housing units in metropolitan Seoul, according to KOCER's Seo Jong Gyun. Communal toilets are located outside the dwellings. Residents, many of whom are families, pay no rent. According to a KOCER report, people are often forced to squat in vinyl houses because of business failure, job loss, rent increase, illness or eviction. Vinyl house squatters, many of whom work as day laborers, street cleaners and restaurant workers, benefit from stable neighborhood relations and nearby jobs, said urban planning expert Ha, so relocating them to distant public housing creates problems. But forced eviction remains a looming threat because oftentimes the land they occupy is valuable. The housing coalition's Lee, a slim, soft-spoken man in his 30s with black horn-rimmed glasses, drove us down a bumpy alley to reach Jandi Village south of the Han River, where the vinyl houses were dwarfed by the sight of new office towers nearby. Lee tries to help these residents build community organizations that can help advocate for better living conditions, fight eviction and gain legal addresses, which makes them eligible for public services. He also helps some who want to move into public housing. We walked narrow pathways between the flimsy homes. Black electrical wiring link the structures like cobwebs. Years ago a fire destroyed several homes here, and a villager died from bad water, said wiry, middle-aged Suh Yang Suk, head of Jandi Village. The inside of one two-room house, adorned with family photos, was compact, but could accommodate a couch, TV, refrigerator and bed. Suh told me squatters founded this village 20 years ago atop a former city dump. About 42 people live here, but the site is slated for redevelopment. Jandi residents are fighting to stay. "We're a community," Suh said. "Living here is cheap and close to jobs, schools and friends. Public housing is far away and expensive. We want to stay together." Sixty-four year old Na Yang Re was a pioneer here. She had to give up the restaurant she once ran because of knee problems, she said. Her son also lives in Jandi. She worries about eviction. "I like this place. Nobody bothers us. I enjoy small talk with friends." Missionary Park Soonsuk (who also goes by "John") of the Seocho House of Peace, one of eight such houses run by the Seoul Archdiocese Catholic Urban Poor Pastoral Committee, also works with the vinyl house communities, providing them with food and helping them organize as a community. He introduced me to Flower Village in Songpa- gu, where we walked past dusty rows of vinyl barracks. Founded in 1985, the village has 180 residents, many of whom work in construction or restaurants. Outside one of the homes near a noisy freeway off-ramp, we met Kim Young Chul, 68, who lives here with his wife, son and small grandson. He moved here in 1987 after he lost his job. Kim, whose grandson was playing near a pile of used soda cans Kim collects for resale, said he'd like to move out of this village, but lacks the money. Nearby, in Guryong Village, 2,000 squatters' shacks blanket a hillside — home to 10,000 residents. At the village's community center Park and I talked to Sisters Gemma and In Monica, Catholic nuns of the Society of St. Paul who have lived here for seven years. They run a school and supervise home health care in the village. Sister Gemma said Guryong was started in 1977 by evictees, and current residents work for low wages cleaning buildings. Some want to stay, while others hope to leave for better accommodations. There is electricity and water, but Sister Gemma said the village isn‘t clean, and health conditions are poor. In the summer the community toilets smell and there are mosquitoes and flies. She said there are also problems with mold in the walls and rain turns pathways to mush. Park drove us south 15 minutes, then turned onto a dirt road to Dukpang Village, which will be torn down this year. Public rental housing will be built in its place. More than 1,000 squatters, two-thirds of them elderly, live here in 500 vinyl houses. We walked past barking dogs to the home of 89-year-old Park Jong Yeon and his 90-year-old wife Kim Pan Rye, who greeted us warmly. Their small home had a single ceiling bulb and a calendar set on the wrong month. Flies buzzed around us. We sat on the floor. John met the couple a few years ago. They have almost no money, no friends and lack government-issued residents' cards, which would allow them basic rights such as voting. They've lived here 11 years. He's an ex-farmer from Jeolla province. His wife has Alzheimer's. Park visits twice a week, providing them rice, medicine and rides to the doctor. The elderly Park said they are comfortable here, but caring for his wife is tiring. Moving her to a nursing home is too expensive, and they want to stay together. As we said good-bye, the couple followed us outside, bowed and thanked the missionary. "I feel sad about this couple," said John, adding that the new public apartments will be too expensive for them, unless a relative helps. Walking past barking dogs, the advocate said he'll keep helping vinyl house dwellers. "They're appreciative," he said. "And it gives me deep satisfaction." * * * |

||

|

|

||